An Indie Band Comes Home:

A Conversation with Joe Makoviecki

To say that the last two years have been a whirlwind for Joe Makoviecki and Jackson Pines may be an understatement. His indie folk band Jackson Pines have been wowing audiences this year from Philadelphia to Montreal with their original interpretations of Pinelands folk gems like “Mt. Holly Jail” and “Clamdigger’s Blues” while crafting their own original songs inspired by folk legends such as Bright Eyes, Elizabeth Cotten, and Bruce Springsteen. Just last summer, Jackson Pines played the Old Time Barnegat Bay Festival, a showcase at the world-famous Philadelphia Folk Festival, The Westerleigh Folk Festival in New York City, and appeared at the American Contemporary Literature Association’s Annual Meeting in Canada. In addition to his work as a musician and music scholar researching Pinelands folk music, Joe is also an author who has published Hornpipe, a collection of poetry with Moonstone Arts of Philadelphia. Makokviecki and I recently sat down on Google Meet for a wide-ranging conversation ahead of their Perkins House Concert gig on Nov. 8. -Marion Jacobson

MJ: Joe, I have been looking forward to this conversation ever since hearing you guys rock a 19th-century prison song on YouTube. As long as I’ve been following your amazing, boundary-crossing career, you’ve been labeled as indie, folk, folk-rock, and God help us, Americana. How do you define yourselves, or has that been evolving with your new Pinelands-centric projects?

Joe Makoviecki in his earlier days as a traveling musician with the indie folk band Thomas Wesley Stern.

JM: We get called everything under the sun. We simply say we’re an indie folk band because we come from the scene of indie rock and DIY music. We also play original music influenced by the 1960s, 70s and 80s along with folk music from the 1800s to the 1940s. Our band could play a rock club one night, a church in the countryside, a library, and a festival with a rock band, maybe even all in one week. We say that we’re ‘folk’ because of the instrumentation and vocabulary, lyrically and musically. But we also use electric guitar and drums and rock out sometimes.

We grew up playing emo and punk in garages as teenagers. Then we started listening to folk revival artists like Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger. Then one day I actually met Pete Seeger and played with him and it changed my life. I had been considering dropping out of college and touring with my band, and that sealed the deal. We bought a van and have been on the road ever since, for 10 years. It’s been a great journey. [Note: Here Joe references his first indie band, Thomas Wesley Stern.] We spent six years on the road.

Before forming Jackson Pines, Joe had another indie folk band. It was called Thomas Wesley Stern. After they broke up, Black stayed on as Joe’s main sideman and bass player in Jackson Pines.

When that band broke up, (bass player) James Black I stayed together as Jackson Pines and started recording material for a new album. These songs were based on stories of our hometown, stories we knew and stories we were told. The first ten songs just really felt like a microcosm of a larger world, although really descriptive of where we grew up in the Pine Barrens, specifically Jackson, New Jersey.

A lot of the songs tended to come back to stories that are passed down family lines. Stories that a grandpa would tell a grandson, a lot of our songs tend to be about grief. And about death, because of things we experienced. I lost both of my parents at the age of 29. We sing about love, death, grief and hope.

As the years went on, we went from writing and performing only original music, to adding in a folksong that was literally from the town where we were from, Jackson; and the county we’re from, Ocean, as well as bordering Burlington County. Five years in, the name Jackson Pines keeps becoming more and more relevant, even though we picked it a long time ago.

MJ: What are the stories that really stick with you and shape your music?

JM: The stories that people told each other while hunting or drinking beer around a fire in the middle of the night: stories of a murder that happened 100 years ago. We found an actual Pine Barrens murder ballad that’s been sung by people Burlington & Ocean Counties.

On our latest records, Pine Barrens Vol. 1 & Vol. 2, we recorded a few of the songs that we found as part of the Merce Ridgway Jr. and the Pine Hawkers cassette tape, recorded in 1980s by [Rutgers professor] Dr. Angus Gillespie. It sent us on this rabbit hole of learning all these old songs, and going out of our way to get permission to record all these songs from Arlene Ridgwaym Merce Jr.’s widow and bandmate. One of these songs is a murder ballad called “Julie Jane.” There are old country songs from the Barnegat Bay, love songs from the Pines, prison songs, Scots-Irish ballads, many songs about missing your childhood home. We’ve spent last two years recording our own versions of these songs and reviving them.

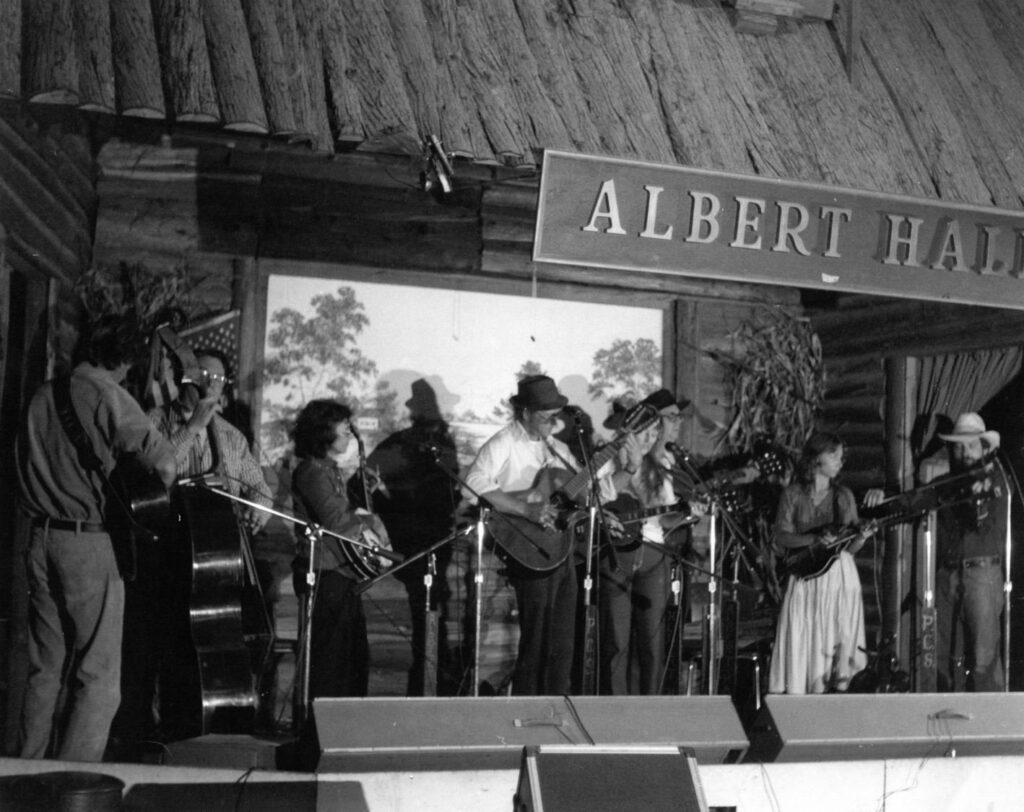

Located in a former cattle auction house, Albert Music Hall in Waretown, NJ has been a venue for country, folk and bluegrass music for decades.

Growing up, we couldn’t really find any folk music from the Pines at all. As teens, we really just played music of the American folk revival. It wasn’t until going to Albert Music Hall in 2011 that we really started to uncover a rich history of New Jersey folk music. It’s kind of the archive and repository and the live stage that’s preserving a large percentage of that music today. If it weren’t for Albert Hall, today we wouldn’t have been able to make these records in as much detail as we have. They are the archive with old documentation of photos, handwritten notes, minutes of their old meetings, and original recordings that they sell to raise money for their nonprofit [the Pinelands Cultural Society]. This helped us put the magnifying glass on some of the old music and explore it more freely than if all we had were a recording.

When we record these Pine Barrens folksongs, we rarely do a version that’s identical to the original version. Reason is, that archive already exists. We’re not really trying to duplicate, but to give some of the songs a breath of fresh air. When there’s already a recording like in the Merce Ridgway Archive, we feel like it’s almost our duty to reimagine a song within reason and within respectful bounds. It usually means a tempo shift, whether we make it faster or slower, for effect.

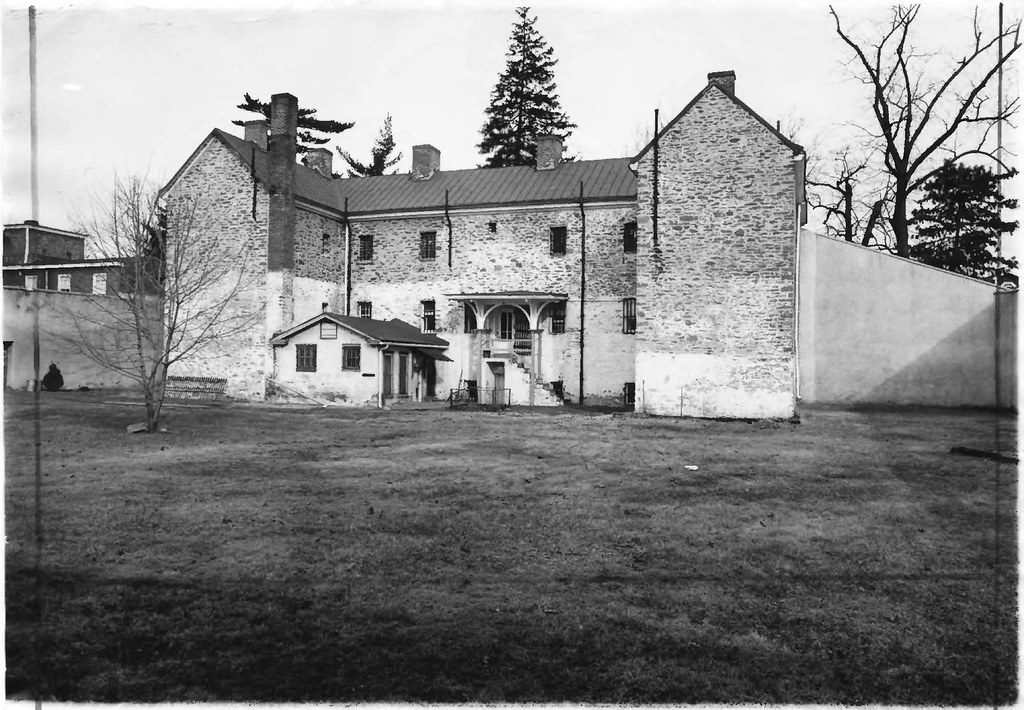

The old Mount Holly Jail, now Burlington County Detention Center

Let me give you an example. Merce Jr. recorded “Mt. Holly Jail” as a slow waltz, and we recorded it as a four-on-the-floor skiffle number. It’s always been intentional, never willy nilly. When we make a change, we do it with a lot of discernment and a lot of care for the material, in hopes that what we do lifts it up and maybe will prod some ears that may not have listened as closely. It’s trying to do something new with what folk music is trying to do.

We’re tapping into this larger movement that started 80 years ago with the folk revival. It said, folk music is important for all THESE reasons. That made a certain percentage of the material canonized. For better or worse, things get flattened. Meanings get lost. Things become trivialized. Right now, I think, we’re on the cusp of a new folk revival that will focus on the gaps. Everywhere people play music together, there’s some kind of folk music tradition. It doesn’t have to be from the South, from Tennessee. It could be from anywhere. The suburbs of Illinois, the cities of Arizona, it could be made on laptops for all I care.

Traditions are everywhere. We’re using the music from where we grew up to kind of show that it’s worth digging in your own backyard and find your own folk traditions, whether it’s Queens, New York or the middle of the Mississippi Delta. Wherever there’s people, there are these histories of musicians who came from there. The more we tap into that, the less we will need to rely on the music industry. There was a lot of music happening everywhere before pop music washed it away.

MJ: The folk music revival made the music very monochromatic, very homogenized.

JM: Yes, folk music has become very “popified.” Bluegrass had to only be this one thing from this one town in Kentucky, but it forgot all the hundred counties around it that might have played bluegrass a little bit differently, because one or two bands started a trend, and there is nothing wrong with that.

Pine Grove, Albert D. Horner. From the 2023 exhibition A Pinelands Portrait at the Stockton Art Gallery

Now we have the decentralization of the industry happening, which the labels hate. We are going to see and learn a lot more history about a lot more local music. We’re going to find it’s a lot more interesting than a lot of the more popular stuff. Not to take away from the Carter Family or the traditions of bluegrass or Robert Johnson—they’re all important and part of the story. I think we’re going to have more histories of what we consider local folk music. Ours is only one piece of the puzzle.

MJ: What does it mean to you to be a voice for Pine Barrens culture?

Merce Ridgway and the Pine Hawkers. Legendary bayman/Renaissance man who shaped Pinelands folk music and made sure it stuck around to inspire Jackson Pines and future generations of musicians and folk music fans.

The Pinelands has been misrepresented for so long and it’s done a lot of damage over time. One governor actually campaigned on “segregating” the people of the pines, and won the 1913 election. The Pinelands may have been culturally isolated, but it was never a cultureless place. People had their own songs, their own dances, their own entertainment, and ways of keeping themselves interested in life. We still have some of the folkways intact, the baskets made from hickory whips, charcoal making, flower and blueberry picking and the music. That was the only upside of isolation. We can still celebrate that culture that lasted untouched, from the Revolutionary War until the 1950s.

We’re glad to be playing music of our home, whether it’s “Mt. Holly Jail” from the 1860s or a song James and I wrote six months ago. And we’re glad to keep doing it in the name of Jim Albertson, Merce Ridgway Jr., Lillian Lopez and all those people who came before us.

MJ: What are you most proud of in your career so far?

Of all the things I’m most proud of is the way that James, me and the backing band that we have now have been make art in a more joyful more focused way than we ever have before. And I’m just really proud the guys for the way we’ve survived emotionally. For ten years, we’ve been rejected from labels and big festivals. We’ve been told our music isn’t right, isn’t good enough for certain things. I’m proud of the way we haven’t let our failures—or our successes—get to us. It’s not easy being a band in any form today. I’ve been proud of the way we’ve been able to navigate and do it with joy.

Marion Jacobson is Director of the Perkins Folklife Center who regularly blogs at Perkins Perspectives, the Perkins Center for the Arts Blog. Read more at perkinsarts.org/blog.

The Folklife Blog is a co-sponsored project of the Perkins Folklife Center and New Jersey State Council on the Arts and its partner agency, the National Endowment for the Arts. Additional support is provided by the Perkins Conservatory.